Volume 1, Issue 4

Breaching the Walls: Military Strategy in the Babylonian Siege of Jerusalem

By Jacob A. Majure

is a fourth-year student majoring in History with a Secondary Education minor. He is primarily interested in research about European cultural history and antiquity. His research advisor is Dr. Shimon Gibson from the Department of History.

Abstract

The city of Jerusalem fell to a Babylonian siege in 586 B.C. Historians recognize the validity of the siege but put little effort into an analysis of the siege tactics utilized by the Babylonians. Most historical knowledge of the sieges comes from biblical accounts within the books of Ezekiel, Jeremiah, and 2 Kings. However, in 2019, University of North Carolina at Charlotte students uncovered artifacts confirming accounts of the siege at UNCC’s dig site in Jerusalem. Among the artifacts, UNCC students discovered a Scythian arrowhead and a golden earring in an ashen layer. The implications of this finding further validate the biblical accounts. This discovery allows historians to revisit the siege with a clearer view of the events of the conquest. This paper analyzes biblical accounts, prior historical research, and newfound artifacts, alongside a historical understanding of the siege methodology of the time, to establish a picture of the two years Jerusalem spent under siege. This paper uses these sources to paint a portrait of the methodology employed by King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon during the siege. Such as, what wall the Babylonians breached the city from, what tools they used to breach the wall, and why the Babylonians “hesitated” following the breach. This paper proposes a theory of exact methods used by the Babylonians to conduct the siege that led to the destruction of one of the most historically significant cities in the world.

Neo-Babylonian Empire, Modern Excavations, Biblical Archaeology, Ancient Military Tactics, Mount Zion Project

Introduction

Jerusalem stands today after surviving assaults from the Persians, Romans, Assyrians, Greeks, and Babylonians. Jerusalem stood firm against Sennacherib and the Assyrians in 701. However, in 587/586 BC, the Neo-Babylonian empire besieged and destroyed the city. The Babylonians, led by King Nebuchadnezzar II, destroyed and burned down all of Jerusalem. The siege left the central city of the kingdom of Judah in ruins. Until recently, biblical accounts alone provided historical context to the siege. The siege is mentioned throughout the Old Testament in the books of Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and 2 Kings.

However, in 2019, UNC Charlotte students excavated artifacts that potentially confirm the utter devastation Jerusalem faced 2,500 years ago. The university students discovered a Scythian arrowhead and a gold earring in an ashen layer. While the biblical sources provide substantial evidence, they include potential biases that might impact an objective understanding of the siege. For example, the biblical accounts have a clear negative view of the reigning king of Judah, Zedekiah; because of this, they attribute the siege to Zedekiah’s unholiness. With their negative view of Zedekiah, it is difficult to understand the deeper reasoning behind Nebucadnezzar’s actions. The discovery of new evidence at UNCC’s dig site provides clarity and confirmation to the potentially biased sources. This paper will show how these findings further enforce existing historical impressions from biblical accounts. These findings and their confirmation of biblical sources make revisiting the history of the siege a necessity.

Few historians have viewed the siege from a military history perspective. This perspective allows for a deeper analysis of the strategic decisions made by Nebuchadnezzar II, contrasting his successful siege with his unsuccessful attempt a decade prior. Through the use of primary and secondary source evidence, this paper seeks to paint a picture of the siege methodology and timeline of the siege.

This paper will analyze biblical accounts, prior historical research, and newfound artifacts, alongside historical understanding of siege methodology at the time to establish a vivid picture of the two years the Babyloniand spent besieging Jerusalem. By examining the fortifications of Jerusalem and the armaments of the Babylonians, this paper will propose a theory of the methods used by the Babylonians to conduct the siege.

Historical Context

Dating the Siege

Many accounts date this siege as 587 BC, while others date it to 586 BC. This conflict arises from confusion and lack of information from accounts. Typically, dates within the Old Testament biblical text are given as years since the ruler came to power. For example, the book of Jeremiah dates the second Babylonian siege of Jerusalem “in the ninth year of Zedekiah king of Judah, in the tenth month.” The conflict arises when trying to place the time of Zedekiah’s rise to the throne. In the text, the new year marks Zedekiah’s rise to power. However, the text does not clarify whether this refers to the Tishrei or the Nisan new year. For clarity, going forward, this essay assumes the use of the Nisan calendar. That places the completion of the siege in August of 587 BC.

Dominance of the Babylonian Empire

The Babylonian empire under Nebuchadnezzar II imposed its power upon the kingdom of Judah and the surrounding area. The Babylonian Empire filled the gap left by the fall of the Assyrian Empire in the seventh century. Historian D.J. Wiseman described Nebuchadnezzar after gaining power as “march[ing] about unopposed.” Nebuchadnezzar goes on to be described as the just king. As he established his dominance in the Near East, he found resistance in Jerusalem.

Jehoiakim ruled as the King of Judah during the late seventh and early sixth century BC. He operated Jerusalem as a vassal state of Egypt until 605 BC when Nebuchadnezzar II forced Jehoiakim into Babylonian allegiance. Nebuchadnezzar intended for Jehoiakim to “reinforce the southern border.” In the early sixth century, Jehoiakim expressed his disdain for his new ruler, Nebuchadnezzar II. Jerusalem was subsequently besieged by Babylon in 597 BC. Nebuchadnezzar placed Zedekiah in power as the new ruler. This laid the foundation for Zedekiah’s rebellion against Nebuchadnezzar II just a decade later and the siege of 587/586 BC, which this essay focuses on.

Methods of Siege Warfare

To conduct a siege, military tacticians cut off supply lines into a city, apply pressure to city walls, and attempt to breach city walls. When besieging a city, the besiegers seek to starve the besieged city of resources and force a surrender. Siege warfare requires patience. Few sieges conclude in less than a year; when they do, it arises from surrender or diplomacy. The final goal of a siege is to force a surrender or to breach the city walls.

The first important step in a siege is a blockade. The army besieging the city creates a blockade to prevent resources from entering the city. These resources might include food, water, and people. By preventing anyone from entering or exiting the city, they ensure that the interior population loses the strength to continue resistance. Historians note these methods in the siege of Megiddo, and even centuries later, in the sieges done by Sennacherib and Nebuchadnezzar II. Besieging a city was a lengthy process. The barricade involved much more than positioning soldiers around the city walls. It involved the construction of structures and fortifications. The main focus of the blockade was placed on the gates and critical points of escape around the city. As described in this Egyptian royal inscription. “They measured the town, surrounded [it] with a ditch, and walled [it] up with fresh timber from all their fruit trees.” The entire method focuses on entrapping the city, as described best by Sennacherib,

Despite the goal being stalemate, sieges include active assaults on the walls and gates of the besieged city. Active assaults force the city to use vital and scarce resources to retaliate. The besieging force seeks to force negotiations and to create the means for a surrender.

Diplomacy also played a significant role in siege warfare. Sieges potentially lasted years on end, so leaders sought to negotiate to end the long process before the city and population were further damaged. Throughout history, negotiations arising from sieges led to compromise, treaties, and surrender.

If negotiations fail, the invading force might decide to attempt to breach the city walls. Popular media often includes battering rams in depictions of siege warfare. These large devices struck city gates until they crumbled and allowed entry. In many instances, geographic features prevented sieging forces from reaching city walls for the use of battering rams. In these circumstances, many armies constructed siege ramps. These large mounds of dirt allowed troops to reach walls that had geographic advantages so that battering rams could be used to bring down the walls.

Despite their popularity, armies did not rely entirely on battering rams for breaching city walls. Certain cities, with walls as thick as four meters, rendered battering rams ineffective. Instead, sieging forces relied on sapping devices, another tool for breaching walls, which saw frequent use during the sixth century BC. An inscription depicting the siege of Lachish shows the use of sappers by the Assyrians to undermine the wall. When sapping a wall, engineers dug a deep crater beneath a portion of the city walls, then they chipped away at the wall’s foundation. Eventually, this collapsed the wall, allowing entry into the city.

Historically Adjacent Sieges

Jacob H. Katzenstein’s research on the siege of Tyre relates closely to the Babylonian siege of 587 BC. This siege was conducted during the same time period of the early sixth century BC. At this time, the Babylonians besieged the city of Tyre. The context of this siege and the mechanics of it contribute to a historic understanding of the formalities within Babylonian siege warfare.

Similarly, the sieges of the Assyrians in the early eighth century BC show further methods of siege warfare. The siege of Lachish conducted by the Assyrians in 701 contributes to the wider understanding of siege warfare methods of that time. Similarly, it is relatively close to Jerusalem, to the southwest, so the Assyrians conducted the siege with methods common to the region. The Lachish siege required the use of a siege ramp, which was constructed to breach the city. The siege ramp at Lachish left evidence still visible today. Due to the lack of similar evidence in Jerusalem, researchers find it unlikely that a siege ramp was used there. This rules out the southern and eastern walls for breach of Jerusalem. If the Babylonians breached these walls, evidence of a ramp to traverse the Kidron and Sillom valleys would be present.

In 604 BC, Nebuchadnezzar used his immense military strength to destroy the city of Ashkelon. As a coastal city, it would have been a challenge similar to Tyre. That is because it had easier access to imports of resources. It also had support from Egyptian forces. Nebuchadnezzar, in his first year, was able to destroy the city of Ashkelon, cementing his place as a powerful military ruler. Research from Alexander Fatalkin at Tel-Aviv University shows that Ashkelon was very well fortified and militarily powerful. Nebuchadnezzar attacked in the winter months to prevent the possibility of Egyptian reinforcements being sent by water. This strategy reflects the military mind of Nebuchadnezzar. Similarly, the confidence of attacking within the winter months implies a strong military force.

Geographic and Natural Features of Jerusalem

Jerusalem benefits from its many natural features that contribute to the fortifications. The Kidron and Hinnom valleys act as two of the most important natural siege deterrents. The Kidron Valley runs parallel to the east side of the Temple Mount and down past the city of David. Similarly, the Hinnom valley runs adjacent to the south walls of the city. The locations of the city in relation to the valleys forced any attacker to focus assault on the western or northern wall. Nearby springs also allowed for ease of access to water. The Gihon spring was just outside the eastern wall. In preparation for the Assyrian siege of 701, Hezekiah had the spring blocked up so that it was inaccessible from the outside. Hezekiah’s tunnel allowed the water to be accessed inside the walls at the pool of Siloam.

The Siege

Jerusalem’s Fortifications

Jerusalem previously prepared fortifications for coming sieges from Assyria. For that reason, the city possessed many resources to outlast a potential siege, so Zedekiah felt little need for additional fortification. Modern remains of the city walls used can be found in the Jewish quarter. Such as the middle gate, discussed in Jeremiah 39:3, “Then all the officials of the king of Babylon came and took seats in the Middle Gate: Nergal-Sharezer of Samgar, Nebo-Sarsekim a chief officer, Negal-Sharezer a high official and all the other officials of the king of Babylon.” The remains of the gate highlighted in this passage allow historians to speculate about the city’s fortifications.

The portion of the gate remaining is an “L” shaped wall. The wall itself sits just under five meters thick. The stone-constructed gate would have been built up into a defensive tower. Archers watched for potential threats while positioned atop these towers. Historians find towers such as this across many fortified cities at the time. For example, one Historian described the city of Ashkelon as having “as many as 50 towers on its land side.” Being a similarly sized city and being prone to sieges, one could then extrapolate that Jerusalem possessed similar fortifications. With towers positioned every 20-30 meters. These towers created a formidable defensive structure when coupled with the geographic advantages the city already possessed.

The Hinnom and Kidron Valleys additionally fortified the southern and eastern walls. To breach this, the Babylonians needed to create a siege ramp so that the siege works could reach the wall. This paper suggests that Babylonians did not assault these walls because of the lack of evidence of siege ramp construction. In a previous assault, the city fortified its western wall beyond the other three walls. For this reason, it is unlikely that Nebuchadnezzar II attacked from the west. This leaves the northern wall as the weakest point and most likely the one that received the brunt of the Babylonian assault.

The Gihon spring lay outside the city walls and acted as a key water source for the entire city. The city fortified the spring previously for the Assyrian siege in 701 to prevent attackers from accessing the spring. Then Jerusalem engineers dug the Hezekiah tunnel under the wall to access the spring. This spring supplied the city with a stable water supply throughout the two-year siege. For these reasons, the only limiting factor within the fortifications was the food supply and the need to defend the northern wall properly.

Babylonian Armaments

Despite no evidence of siege ramps, Ezekiel 17:17 says, “Pharaoh with his mighty army and great horde will be of no help to him (Zedekiah) in the way, when ramps are built and siege works erected to destroy many lives.” With no clear remains of a siege ramp, this verse likely refers to the creation of small mounds to be used as siege ramps that someone later removed or that the Babylonians used as some form of temporary siege ramp substitute. However, in alternate translations, this text is translated as “casting up mounts, and building forts, to cut off many persons.” So, with this in mind, it likely referenced the Babylonians laying the groundwork for siege towers and armaments.

Assaulting armies built siege structures on location because the armies understood the impracticality of traveling with the structures. In most scenarios, the assaulting force used local resources to build the structures. With the past few sieges occurring with the use of siege towers in Jerusalem, the area likely possessed local wood that assaulters used for construction. “The towers were probably assembled beyond the range of the defenders’ fire and only brought close to the wall later.” At the time, engineers referred to the siege structures as nēpešu. The nēpešu were flammable and slow to transport.

Based on an analysis of adjacent sieges, one can expect that Nebuchadrezzer surrounded nearby outposts of the city to cut off resources. In the siege of Lachish, a neighboring city destroyed in Nebuchadnezzar’s campaign of 587 BC, Nebuchadnezzar II employed a similar tactic to eliminate their communication and supply lines. Once this entrapment was complete, Nebuchadnezzar II began his assault on the city.

Twenty Months Trapped

Accounts put the siege at just under two years. Jeremiah 39:1 puts the beginning of the siege in the tenth month of the ninth year of Zedekiah’s reign. The breach of the walls was dated as the ninth of Tammuz of Zedekiah’s eleventh year. Tammuz occurs in June and July. With the conquest of the temple that occurred a week later, August 5, 587 BC, you can place the time of the breach in late July. The siege would have been around 20 months in length. The Babylonians needed to complete their construction of siege works and the tightening of the supply lines before they fully assaulted the walls.

With intentions of strangling the city’s supplies, Nebuchadnezzar II strengthened his hold around the city and cut off communications with allies within the first few months. The city fell to a weakened state of famine and hunger. Then the Babylonians breached the walls, and Nebuchadnezzar requested to meet with Zedekiah to discuss surrender.

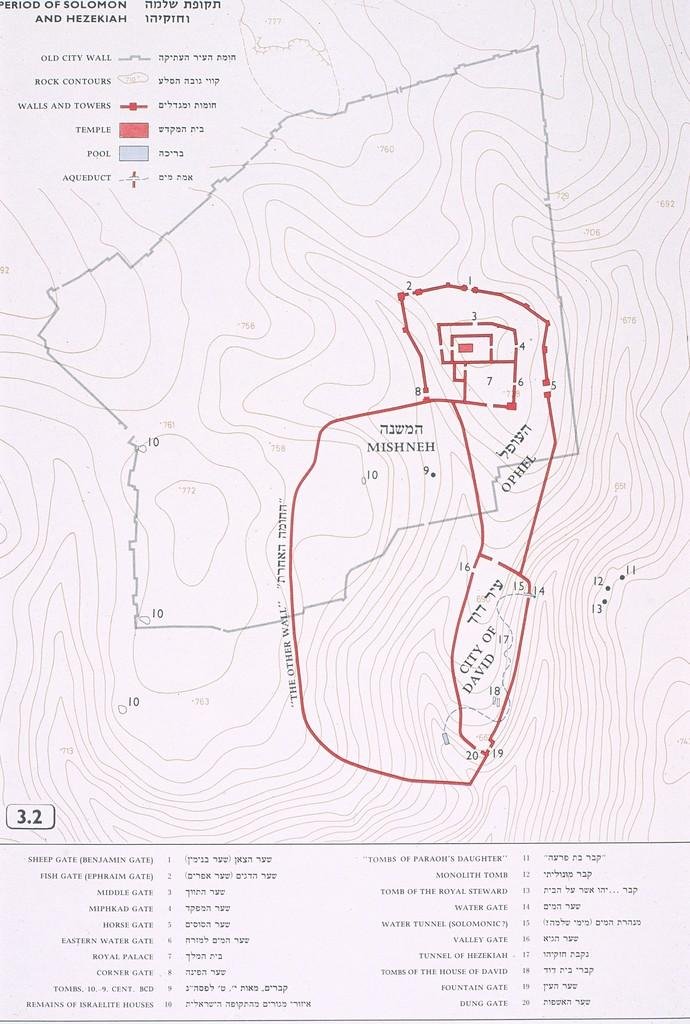

Calm before the Conquest

After the two-year siege, the Babylonians breached the wall. However, they waited a month before burning and pillaging the city. Donald Wiseman suggests that this pause resulted from attempts at brokering peace. As previously stated, he based this claim on Jeremiah 39:3, which mentions the gathering of all of Nebuchadnezzar II’s officials at the north gate of Jerusalem. See the illustrations section for a period-accurate map of Jerusalem that shows the potential location of this gate. However, when viewed in context, these verses point to a different interpretation of the month pause.

Wiseman’s theory confirms the biblical accounts that suggest unrest within the population. However, the struggle of the population existed separate from the negotiation. Jeremiah 37:21 in the KJV says, “Then Zedekiah the king commanded that they should commit Jeremiah into the court of the prison and that they should give him daily a piece of bread out of the bakers’ street until all the bread in the city were spent. Thus Jeremiah remained in the court of the prison.” Wiseman refers to this verse as evidence of hunger and famine. He felt that this great famine and struggle resulted in the negotiations that caused the month-long armistice. The verses describe the destitute situation within the city during the siege. Jeremiah makes it clear that beyond hunger, people experienced plague, pestilence, and famine.

The month-long delay instead resulted from the pursuit of Zedekiah. The verses following Jeremiah 39:3, which Wiseman cited, give insight into this. When Zedekiah saw that they had gathered at the north gate, he fled with his soldiers out of a southern gate. This is seen in Jeremiah 39:4, “when Zedekiah the king of Judah saw them, and all the men of war, then they fled, and went forth out of the city by night, by way of the king’s garden, by the gate betwixt the two walls: and he went out the way of the plain,” His escape route led him through a gate to the south of the city near the city of David. From there, Zedekiah fled towards the plains of Jericho, where the Babylonians captured him a month later. This is the reason that there was a delay before the siege. He was caught and taken back to Babylon to be imprisoned. This account refers to all of Nebuchadnezzar’s army pursuing Zedekiah and the remaining soldiers. After his capture, the city was destroyed. This theory aligns with biblical evidence and explains Ezekiel and Jeremiah’s disdain for Zedekiah. They blamed him for the city’s destruction, not just for his initial disobedience but also for his evacuation when Nebuchadnezzar II offered to meet and negotiate diplomatically. By refusing to meet with Nebuchadnezzar II, Zedekiah brought about the utter destruction of his capital city.

Here goes your text … Select any part of your text to access the formatting toolbar.

Jerusalem’s Fortifications

Jerusalem previously prepared fortifications for coming sieges from Assyria. For that reason, the city possessed many resources to outlast a potential siege, so Zedekiah felt little need for additional fortification. Modern remains of the city walls used can be found in the Jewish quarter. Such as the middle gate, discussed in Jeremiah 39:3, “Then all the officials of the king of Babylon came and took seats in the Middle Gate: Nergal-Sharezer of Samgar, Nebo-Sarsekim a chief officer, Negal-Sharezer a high official and all the other officials of the king of Babylon.” The remains of the gate highlighted in this passage allow historians to speculate about the city’s fortifications.

The portion of the gate remaining is an “L” shaped wall. The wall itself sits just under five meters thick. The stone-constructed gate would have been built up into a defensive tower. Archers watched for potential threats while positioned atop these towers. Historians find towers such as this across many fortified cities at the time. For example, one Historian described the city of Ashkelon as having “as many as 50 towers on its land side.” Being a similarly sized city and being prone to sieges, one could then extrapolate that Jerusalem possessed similar fortifications. With towers positioned every 20-30 meters. These towers created a formidable defensive structure when coupled with the geographic advantages the city already possessed.

The Hinnom and Kidron Valleys additionally fortified the southern and eastern walls. To breach this, the Babylonians needed to create a siege ramp so that the siege works could reach the wall. This paper suggests that Babylonians did not assault these walls because of the lack of evidence of siege ramp construction. In a previous assault, the city fortified its western wall beyond the other three walls. For this reason, it is unlikely that Nebuchadnezzar II attacked from the west. This leaves the northern wall as the weakest point and most likely the one that received the brunt of the Babylonian assault.

The Gihon spring lay outside the city walls and acted as a key water source for the entire city. The city fortified the spring previously for the Assyrian siege in 701 to prevent attackers from accessing the spring. Then Jerusalem engineers dug the Hezekiah tunnel under the wall to access the spring. This spring supplied the city with a stable water supply throughout the two-year siege. For these reasons, the only limiting factor within the fortifications was the food supply and the need to defend the northern wall properly.

Babylonian Armaments

Despite no evidence of siege ramps, Ezekiel 17:17 says, “Pharaoh with his mighty army and great horde will be of no help to him (Zedekiah) in the way, when ramps are built and siege works erected to destroy many lives.” With no clear remains of a siege ramp, this verse likely refers to the creation of small mounds to be used as siege ramps that someone later removed or that the Babylonians used as some form of temporary siege ramp substitute. However, in alternate translations, this text is translated as “casting up mounts, and building forts, to cut off many persons.” So, with this in mind, it likely referenced the Babylonians laying the groundwork for siege towers and armaments.

Assaulting armies built siege structures on location because the armies understood the impracticality of traveling with the structures. In most scenarios, the assaulting force used local resources to build the structures. With the past few sieges occurring with the use of siege towers in Jerusalem, the area likely possessed local wood that assaulters used for construction. “The towers were probably assembled beyond the range of the defenders’ fire and only brought close to the wall later.” At the time, engineers referred to the siege structures as nēpešu. The nēpešu were flammable and slow to transport.

Based on an analysis of adjacent sieges, one can expect that Nebuchadrezzer surrounded nearby outposts of the city to cut off resources. In the siege of Lachish, a neighboring city destroyed in Nebuchadnezzar’s campaign of 587 BC, Nebuchadnezzar II employed a similar tactic to eliminate their communication and supply lines. Once this entrapment was complete, Nebuchadnezzar II began his assault on the city.

Twenty Months Trapped

Accounts put the siege at just under two years. Jeremiah 39:1 puts the beginning of the siege in the tenth month of the ninth year of Zedekiah’s reign. The breach of the walls was dated as the ninth of Tammuz of Zedekiah’s eleventh year. Tammuz occurs in June and July. With the conquest of the temple that occurred a week later, August 5, 587 BC, you can place the time of the breach in late July. The siege would have been around 20 months in length. The Babylonians needed to complete their construction of siege works and the tightening of the supply lines before they fully assaulted the walls.

With intentions of strangling the city’s supplies, Nebuchadnezzar II strengthened his hold around the city and cut off communications with allies within the first few months. The city fell to a weakened state of famine and hunger. Then the Babylonians breached the walls, and Nebuchadnezzar requested to meet with Zedekiah to discuss surrender.

Calm before the Conquest

After the two-year siege, the Babylonians breached the wall. However, they waited a month before burning and pillaging the city. Donald Wiseman suggests that this pause resulted from attempts at brokering peace. As previously stated, he based this claim on Jeremiah 39:3, which mentions the gathering of all of Nebuchadnezzar II’s officials at the north gate of Jerusalem. See the illustrations section for a period-accurate map of Jerusalem that shows the potential location of this gate. However, when viewed in context, these verses point to a different interpretation of the month pause.

Wiseman’s theory confirms the biblical accounts that suggest unrest within the population. However, the struggle of the population existed separate from the negotiation. Jeremiah 37:21 in the KJV says, “Then Zedekiah the king commanded that they should commit Jeremiah into the court of the prison and that they should give him daily a piece of bread out of the bakers’ street until all the bread in the city were spent. Thus Jeremiah remained in the court of the prison.” Wiseman refers to this verse as evidence of hunger and famine. He felt that this great famine and struggle resulted in the negotiations that caused the month-long armistice. The verses describe the destitute situation within the city during the siege. Jeremiah makes it clear that beyond hunger, people experienced plague, pestilence, and famine.

The month-long delay instead resulted from the pursuit of Zedekiah. The verses following Jeremiah 39:3, which Wiseman cited, give insight into this. When Zedekiah saw that they had gathered at the north gate, he fled with his soldiers out of a southern gate. This is seen in Jeremiah 39:4, “when Zedekiah the king of Judah saw them, and all the men of war, then they fled, and went forth out of the city by night, by way of the king’s garden, by the gate betwixt the two walls: and he went out the way of the plain,” His escape route led him through a gate to the south of the city near the city of David. From there, Zedekiah fled towards the plains of Jericho, where the Babylonians captured him a month later. This is the reason that there was a delay before the siege. He was caught and taken back to Babylon to be imprisoned. This account refers to all of Nebuchadnezzar’s army pursuing Zedekiah and the remaining soldiers. After his capture, the city was destroyed. This theory aligns with biblical evidence and explains Ezekiel and Jeremiah’s disdain for Zedekiah. They blamed him for the city’s destruction, not just for his initial disobedience but also for his evacuation when Nebuchadnezzar II offered to meet and negotiate diplomatically. By refusing to meet with Nebuchadnezzar II, Zedekiah brought about the utter destruction of his capital city.

Summary and Conclusion

he evidence presented in the previous sections both supports and challenges existing theories of the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem in 587 BC. The findings at the UNCC dig site confirmed the biblical evidence. The sieges of Lachish and Tyre show the methods of siege warfare used by the Babylonians. This provides the clearest evidence to build a theory for their methods in the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem in 587 BC. Donald Wiseman provided the clearest analysis of the siege events in his work Nebuchadrezzar and Babylon, but his negotiation theory overlooks the biblical context from Jeremiah 39. This evidence contributes to a strengthened understanding of the second Babylonian siege of Jerusalem. With all of this evidence in mind, this section will provide a short summary and timeline of events as they can now be more deeply understood.

Nebuchadnezzar II demanded the destruction of Jerusalem as penance for King Zedekiah’s disobedience. He took action against Jerusalem for the second time during his reign as King of the Babylonian Empire, determined for it to be his last. Nebuchadnezzar swiftly mobilized his military forces, which held great experience with siege warfare. This did not take long; they also actively besieged Tyre in the same year. They arrived and began construction of siege works in mid-January of 588 BC.

They formed a blockade around all of the major gates of the city and built fortifications and walls. They cut off outside contact to any small defensive fortifications that Jerusalem may have possessed. The Babylonian engineers built mobile siege towers so that they could roll to the walls from outside of arrow range. The Egyptian forces possibly arrived during this time and caused a level of disruption within construction, but nothing substantial.

Jerusalem’s location and prior siege preparations contributed to its strong fortifications. For this reason, Nebuchadnezzar II focused the blunt force of the siege works on the north wall of Jerusalem. Large defensive towers segmented the walls with soldiers and watchmen. The Babylonian engineers likely built the siege towers to a similar height to combat these towers along the walls.

After over a year of continued siege, citizens in Jerusalem began to grow restless as food became more scarce. Hezekiah’s tunnel provided a stable source of water, but the siege eliminated all stable food supply entering the city from surrounding farms. The soldiers defending began to waver and grow weary. Jeremiah references this saying, “He is discouraging the soldiers who are left in this city.” With a starving population and weakened military force, the first year of the siege successfully primed Jerusalem for surrender.

As the city struggled, few soldiers remained to fight and defend. Then, the Babylonians used their siege towers to apply enough force of arrow fire to the defending towers to allow sappers to reach and undermine the northern wall. The scythian arrowhead found at the UNCC Mount Zion dig is likely a remnant of this exchange of arrow fodder. The wall was breached in the last week of July 587 BC. After this, the Babylonians spent a month tracking down and capturing Zedekiah. His dissent, shown in his failure to meet with Nebuchadnezzar II, influenced his decision to burn the entire city.

This account further strengthens historical understanding of the siege and understanding of the books of Jeremiah, 2 Kings, and Ezekiel. The discoveries at the UNCC excavation demanded additional research to be conducted and the topic of the siege to be revisited. This paper seeks to do so with a focus on the military actions and siege methods used by the attacking Babylonian forces.

This topic could be further strengthened by future research into the lives of citizens within Jerusalem during the siege. Specifically their perceptions of Zedekiah. Further research into siege warfare across civilizations would strengthen this research. Potential methods used at the siege of Jerusalem that the Babylonians chose uniquely for that siege and no others, like the large ramp at Tyre. Future archaeological excavations around the middle gate might provide further evidence of the validity of Wiseman’s negotiation theory. There are many ways this topic can be furthered by future research, which would further enrich the historical understanding of Jerusalem. Through deeper study of the old city, a greater understanding can come to light about the siege that led to the fall of the kingdom of Judah.

Acknowledgements

Citations

Albright, W. F. “The Nebuchadnezzar and Neriglissar Chronicles.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 143 (1956): 28–33. https://doi.org/10.2307/1355927.

Ephʻal, Israel. “Nebuchadnezzar the Warrior: Remarks on his Military Achievements.” Israel Exploration Journal 53, no. 2 (2003): 178-191. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27927044?origin=JSTOR-pdf&seq=9#metadata_info_tab_contents.

Ephʻal, Israel. The City Besieged: Siege and Its Manifestations in the Ancient Near East. Leiden: Brill, 2009.

Fantalkin, Alexander. “Why Did Nebuchadnezzar II Destroy Ashkelon in Kislev 604 BCE?” In The Fire Signals of Lachish: Studies in the Archaeology and History of Israel in the Late Bronze Age, Iron Age, and Persian Period in Honor of David Ussishkin, edited by Israel Finkelstein and Nadav Na’aman, 87-112. USA: Penn State University Press, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781575066295-008

Frame, Grant. “A Siege Document from Babylon Dating to 649 B.C.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 51 (1999): 101–6. https://doi.org/10.2307/1359733.

Garfinkel, Yosef et al. “Lachish Fortifications and State Formation in the Biblical Kingdom of Judah in Light of Radiometric Datings.” Radiocarbon 61, no. 3 (June 2019): 695-712. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2227357493/fulltextPDF/F1F034AD45F5400CPQ/1?accountid=12544

Garfinkel, Yosef et al. “Constructing the Assyrian siege ramp at Lachish: Texts, Iconography, Archaeology and Photogrammetry.” Oxford Journal of Archaeology 40, no. 4 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ojoa.12231

Garstad, Benjamin. “Nebuchadnezzar’s Siege of Tyre in Jerome’s ‘Commentary on Ezekiel.’” Vigiliae Christianae 70, no. 2 (2016): 175–192.

Hathaway, James. “Evidence of the 587/586 BCE Babylonian Conquest of Jerusalem Found in Mount Zion Excavation.” Inside UNC Charlotte. August 12, 2019.

Katzenstein, Jacob. The History of Tyre: From the beginning of the second millennium B.C.E. until the fall of the Neo-Babylonian empire in 538 B.C.E. BenGurian: University of the Negev Press, 1997.

Malamat, Abraham. “King Lists of the Old Babylonian Period and Biblical Genealogies.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 88, no. 1 (1968): 163–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/597910.

Matty, Nazek Khaled. Sennacherib’s Campaign Against Judah and Jerusalem in 701 B.C.: a Historical Reconstruction. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016.

Oppenheim, A. L. “‘Siege-Documents’ from Nippur.” Iraq 17, no. 1 (1955): 69–89. https://doi.org/10.2307/4241717.

Wiseman, D. J. Nebuchadrezzar and Babylon. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Appendices

Appendix A

Neo-Assyrian. Siege of Lachish (Judah): Assyrian Sappers Undermine the City Walls, Detail [L.] of Relief from SW. Palace of Sennacherib at Nineveh (Kuyunjik), n.d

Appendix B

Hathaway, James. “Evidence of the 587/586 BCE Babylonian Conquest of Jerusalem Found in Mount Zion Excavation.” Inside UNC Charlotte. August 12, 2019.

Appendix C

N/A. “26- The Middle Gate (of Jeremiah 39:3).” Jerusalem 101, 2022. https://www.generationword.com/jerusalem101/26-middle-gate.html

Appendix A

Jerusalem: Map: Period of Solomon and Hezekiah, c.996-c.586 B.C.E. n.d. Visual Arts Legacy Collection. Artstor. https://jstor.org/stable/community.18136174